Teaching

My teaching philosophy — which draws on over two decades of undergraduate and graduate-level teaching experience (including film, media, theory, language, composition, and practice-oriented courses at BA, MA, and Ph.D. levels) — is closely linked to my conception of an emphatically interdisciplinary field of humanistic study at the nexus of film and media studies, digital arts and humanities, and creative applications of computational media. To do justice to this field and, more specifically, to do justice to the pedagogical and cultural transformations that it has witnessed in conjunction with the advent of digital media, requires an approach that combines historical, theoretical, and practical forms of inquiry from a range of disciplinary orientations: cultural theory, the history and philosophy of technology, literary and narrative perspectives, alongside more specialized areas of film history and theory, but also comics studies, game studies, television studies, and media art.

Here are some of my recent courses:

* * *

Media and the Environment (Stanford 2023, 2025)

How are environmental issues represented in various media, from cinema and television to videogames, VR, and experimental art? And how are these media themselves involved in environmental change? In this course, we look at media and the environment as interlocking parts of a system, inseparable from one another. We might start by asking how, for example, documentary and narrative films portray environmental crises like oil spills, wildfires, or extinction events. From there, however, we will need to investigate the ways that media themselves constitute environments, both metaphorically and literally. We swim in media; it is the air we breathe. Virtually all of our experience and communication take place within the spaces of media. Meanwhile, media-technologies and their infrastructures are increasingly entangled with the material environment: from rare earth metals in our electronic devices to undersea cables that bring us the Internet, digital media in particular are an increasingly significant driver of environmental change. In addition to reading and engaging with a variety of media objects, students will have the opportunity to create their own media objects (video essays, VR projects, experimental artworks, etc.) that shed light on the interrelations of media and the environment.

* * *

Post-Cinema (Duke 2015, Stanford 2017, 2019, 2022)

In this seminar, we will try to come to terms with twenty-first century motion pictures by thinking through a variety of concepts and theoretical approaches designed to explain their relations and differences from the cinema of the previous century. We will consider the impact of digital technologies on film, think about the cultural contexts and aesthetic practices of contemporary motion pictures, and try to understand the experiential dimensions of spectatorship in today's altered viewing conditions. In addition to viewing a wide range of recent and contemporary films, we will also engage more directly and materially with post-cinematic moving images: we will experiment with scholarly and experimental uses of non-linear video editing for the purposes of film analysis, cinemetrics, and a variety of academic and creative responses to post-cinematic media. The course addresses key issues in recent film and media theory and, especially in its hands-on components, encourages experimentation with methods of digital humanities, computational media art, and other creative practices.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

Aesthetics and Phenomenology (Stanford 2019, 2022, 2024)

This course explores central topics in aesthetics — where "aesthetics" is understood both in the narrow sense of the philosophy of art and aesthetic judgment, and in a broader sense as it relates to questions of perception, sensation, and various modes of embodied experience. We will engage with both classical and contemporary works in aesthetic theory, and special emphasis will be placed on phenomenological approaches to art and aesthetic experience across a range of media and/or mediums (including painting, sculpture, film, and digital media). The course seeks to illuminate (theories of) the aesthetic forms and phenomena that are central to our experience of the world. We will engage with these topics through an intensive reading program; each class session will be devoted to the close reading and discussion of a canonical or contemporary work or selection of works.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

German Media Theory (Stanford 2022)

In this seminar, we will interrogate major currents in media-theoretical work from the German-speaking world from the 1980s to today. Starting from the surprisingly controversial term “German media theory” itself — which has been described as “neither a theory nor really centered on media, [while] its Germanness is a contested issue” — we will consider the characteristics that nevertheless make this a recognizable, if internally heterogeneous, category for thinking about media, mediation, and culture. We will pay special attention to the foundational work of Friedrich Kittler, which ranges across literature, film, philosophy, and computers, before turning to the current differentiation into a technology-focused “media archaeology” (Wolfgang Ernst) and the differently inflected formation of “cultural techniques” (Bernhard Siegert), as well as recent articulations of “media philosophy” and other developments in contemporary theory. We will also examine the often absent and/or fraught role of gender, race, and class in this field, as well as attempts to address these issues by such theorists as Ute Holl, Cornelia Vissman, Astrid Deuber-Mankowsky, Annette Bitsch, and Sybille Krämer.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

Media Technology Theory (Co-Taught with Fred Turner, Stanford 2020)

This course aims to introduce and compare key theories of media and media technology. We hope to help students develop their own answers to such questions as, what should we study when we study media? And, how should we think about technology when we're thinking about film, communication, and the arts? The course is a reading seminar, and in that sense will demand that students develop a rich fluency in the literatures we take up. In particular, students will develop an appreciation for the differences between humanistic and social scientific approaches to media, and for the distinctions between theory, analysis and description in otherwise empirical scholarship. Finally, we hope to help students imagine applying a variety of new theoretical lenses to their own empirical research questions.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

How to Watch TV (Stanford 2020, 2022)

"How to watch TV" may seem like the most obvious thing in the world. Yet when we look at the historical development of television as a technological, social, and cultural form, we find that people have engaged with it in a variety of different ways. There is not, in other words, a single right way to watch TV. This is because television itself has undergone transformations on all of these levels: Technologically, changes such as those from black-and-white to color, analog to digital, standard to high-definition, and broadcast to cable to interactive all play a role in changing our relation to what "television" is. Socially, changes in television's integration in corporate and industrial structures, its mediation of political realities, and its ability to reflect and shape our interactions with one another all play a role in transforming who "we" as viewers are. And culturally, varieties of programming including live broadcasting, prerecorded content, and on-demand streaming of news, movies, sit-coms, and prestige drama series all indicate differences and distinctions in what it means to "watch" TV. In this course, we will engage with these and other aspects of television as a medium in order to rethink not only how but why we watch TV.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

Digital and Interactive Media (Stanford 2020)

This course introduces a variety of ways of thinking about digital and interactive media. As examples, we will think about the impact of algorithmic processes on cinema and other moving-image media; we will consider the relation of narrative to interactivity in videogames and related forms; and we will look carefully at the perceptual and embodied relations of human users to computational systems of various sorts. Engaging with a wide range of historical and contemporary media forms (including those used for entertainment, artistic expression, social interaction, politics, work, play, and other things in between), this course hopes to illuminate the transformative roles that digital and interactive media play in our lives.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

Currents in Media Theory (Stanford 2018)

This seminar explores a set of currents in media theory (and related fields), which we will seek to navigate together as a group. We will focus on approaches, discourses, conversations, and paradigms that seek to explain the mediations, modulations, and triangulations of our experience within a changing landscape of technological, social, political, and other forces. Special attention will be given to contemporary works of theory and/or works that are enjoying a renewed contemporary reception. The course seeks to illuminate forms and phenomena of media and mediation that are central to our experience of the world. We will engage with these topics through an intensive reading program; each class session will be devoted to the close reading and discussion of a book of cutting-edge media theory.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

Let's Make a Monster: Critical Making (Co-taught with Paul DeMarinis, Stanford 2018)

Ever since Frankenstein unleashed his monster onto the world in Mary Shelley's novel from 1818, the notion of "technology-out-of-control" has been a constant worry of modern societies, plaguing more optimistic visions of progress and innovation with fears that modern machines harbor potentials that, once set in motion, can no longer be tamed by their human makers. In this characteristically modern myth, the act of making — and especially technological making — gives rise to monsters. As a cautionary tale, we are therefore entreated to look before we leap, to go slow and think critically about the possible consequences of invention before we attempt to make something radically new. However, this means of approaching the issue of human-technological relations implies a fundamental opposition between thinking and making, suggesting a split between cognition as the specifically human capacity for reflection versus a causal determinism-without-reflection that characterizes the machinic or the technical. Nevertheless, recent media theory questions this dichotomy by asserting that technologies are inseparable from humans' abilities to think and to act in the world, while artistic practices undo the thinking/making split more directly and materially, by taking materials — including technologies — as the very medium of their critical engagement with the world. Drawing on impulses from both media theory and art practice, "critical making" names a counterpart to "critical thinking" — one that utilizes technologies to think about humans' constitutive entanglements with technology, while recognizing that insight often comes from errors, glitches, malfunctions, or even monsters. Co-taught by a practicing artist and a media theorist, this course will engage students in hands-on critical practices involving both theories and technologies. Let's make a monster!

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

Game Studies (Stanford 2018, 2018)

This course aims to introduce students to the emerging, interdisciplinary field of game studies. We will investigate what games (including but not limited to digital games) are, why we play them, and what the functions of this activity might be. The bulk of the course will be devoted specifically to digital games, which we will approach from a variety of perspectives: from historical, cultural, industrial/commercial, media-theoretical, and formal (narratological/ludological) perspectives, among others. Thus, we will seek to understand the contexts in which video games emerged and evolved, the settings in which they have been played, and the discourses and practices that have determined their place in social and cultural life. In addition, we will ask difficult questions about the mediality of digital games: What is the relation of digital to non-digital games? Are they both games in the same sense, or do digital media redefine what games are or can be? How do digital games relate to other (digital as well as non-digital) non-game media, such as film, television, print fiction, or non-game computer applications? Of course, to engage meaningfully with these questions at all will require us to investigate theories of mediality (including inter- and transmediality) more generally. Finally, though, we will be interested in the formal and experiential parameters that define (different types of) digital games in particular. What does it feel like to play (various) digital games? What are the relations between storytelling and the activity of gameplaying in them? What is the relation between these aspects and the underlying mechanics of digital games, as embodied in hardware and software? What is the role of the human body, and how are our experiences of gameplay inflected by our social, gendered, and other identifications (and vice versa)?

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

The Video Essay: Writing with Video about Media and Culture (Stanford 2017, 2019, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024)

In this seminar, we will explore what it means to "write with video," and we will learn to make effective and engaging video essays about historical and contemporary audiovisual media. Specifically, we will examine formal, aesthetic, and rhetorical strategies for communicating through video, and we will conduct hands-on exercises using digital video editing software to construct arguments, analyses, and interpretations of film, television, video games, and online media. Compared with text, the video essay offers a remarkably direct mode of communicating critical and analytical ideas. Video essayists can simply show their viewers what they want them to see. This does not mean, however, that it is any easier than an essay composed with ink and paper. Like the written essay, the new technology introduces its own challenges and choices, including decisions about the organization of space and time, audiovisual materials, onscreen text, voiceover commentary, and visual effects. By taking a hands-on approach, we will develop our skills with editing software such as Adobe Premiere Pro and Apple's Final Cut Pro while also cultivating our awareness of the formal and narrative techniques employed in films and other moving-image media. Through weekly assignments and group critique sessions, we will learn to express ourselves more effectively and creatively in audiovisual media. As a culmination of our efforts, we will assemble a group exhibition of our best video essays for public display on campus.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

Seriality (Stanford 2017)

In this seminar, we will think about serial forms and serialization processes across a range of media and investigate their relations to our aesthetic experiences, media-technological apparatuses, and sociocultural formations. We will focus especially on the popular, commercial forms of seriality that have emerged since the nineteenth century and dominated large sections of popular culture in the forms of serialized novels, film and radio serials, and television series. But this investigation will be relevant as well for the study of "high art," or art forms situated outside the realm of "the popular." This is true not only for movements, like Pop Art, that engage explicitly with popular culture, but also for a wide range of artistic practices that are affected or informed by industrial processes and utilize for their expressive or aesthetic purposes the formal techniques of seriality. Ultimately, we may inquire whether there is a deeper relation between seriality and mediality more generally — whether media rely for their conceptual definition or practical efficacy upon a serial interplay between repetition and variation. On the other hand, however, we will attend also to the possible differences between industrial, pre-industrial, and digital forms of serialization and think about the role of seriality in media-historical shifts and transformations. The course seeks to illuminate forms and phenomena that are central to our cultural and aesthetic experience of the world. In addition to engaging with a wide range of readings and viewings assigned by the instructor, participants are invited to contribute actively to the course’s comparative focus with materials, projects, and presentations of their own.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

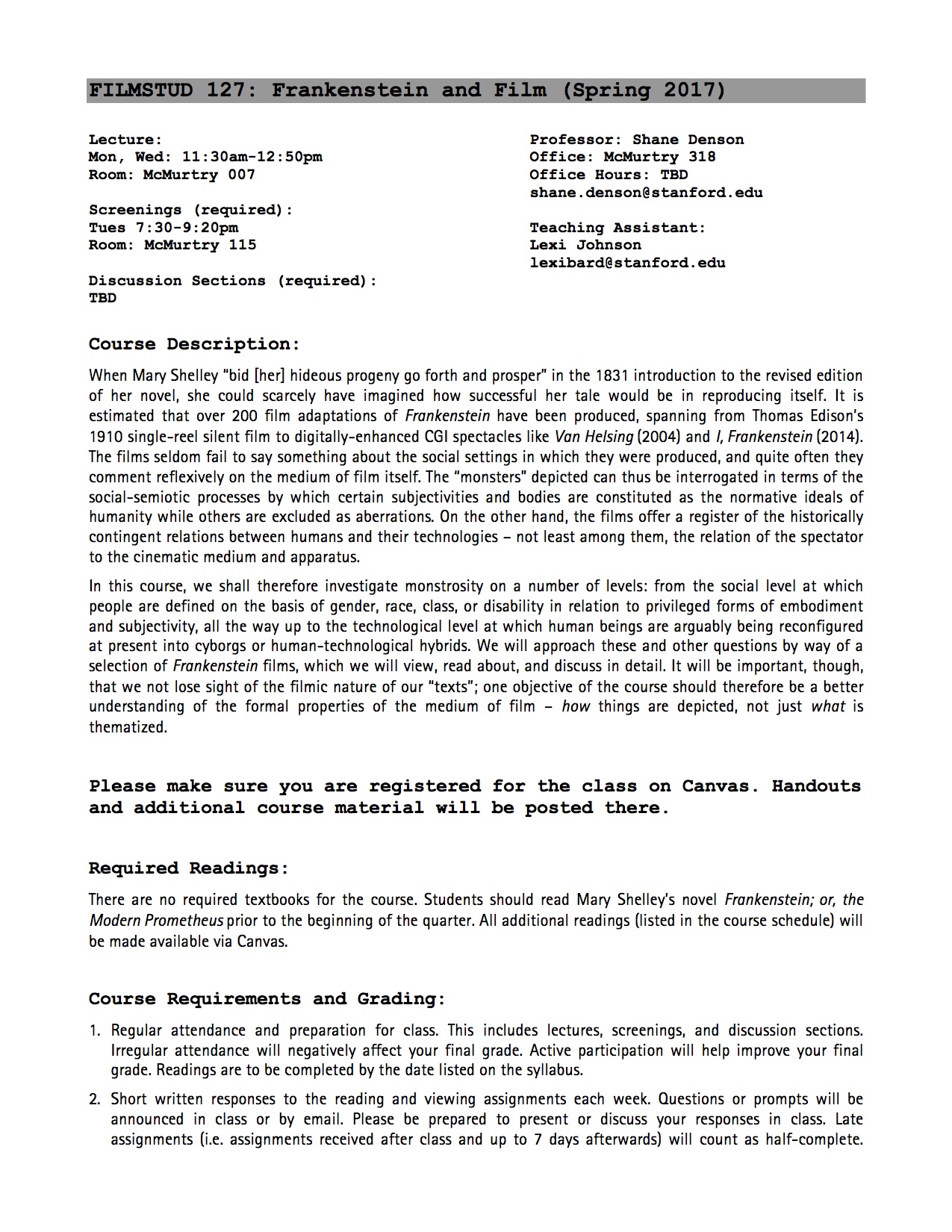

Frankenstein and Film (Stanford 2017)

When Mary Shelley "bid [her] hideous progeny go forth and prosper" in the 1831 introduction to the revised edition of her novel, she could scarcely have imagined how successful her tale would be in reproducing itself. It is estimated that over 200 film adaptations of Frankenstein have been produced, spanning from Thomas Edison’s 1910 single-reel silent film to digitally-enhanced CGI spectacles like Van Helsing (2004) and I, Frankenstein (2014). The films seldom fail to say something about the social settings in which they were produced, and quite often they comment reflexively on the medium of film itself. The "monsters" depicted can thus be interrogated in terms of the social-semiotic processes by which certain subjectivities and bodies are constituted as the normative ideals of humanity while others are excluded as aberrations. On the other hand, the films offer a register of the historically contingent relations between humans and their technologies — not least among them, the relation of the spectator to the cinematic medium and apparatus. In this course, we shall therefore investigate monstrosity on a number of levels: from the social level at which people are defined on the basis of gender, race, class, or disability in relation to privileged forms of embodiment and subjectivity, all the way up to the technological level at which human beings are arguably being reconfigured at present into cyborgs or human-technological hybrids. We will approach these and other questions by way of a selection of Frankenstein films, which we will view, read about, and discuss in detail. It will be important, though, that we not lose sight of the filmic nature of our "texts"; one objective of the course should therefore be a better understanding of the formal properties of the medium of film — how things are depicted, not just what is thematized.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

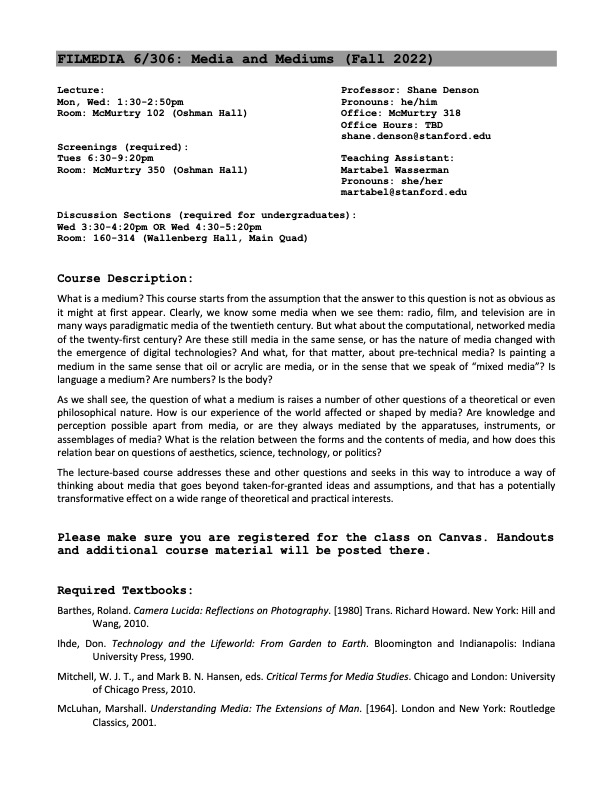

Media and Mediums (Stanford 2016 - 2024)

What is a medium? This course starts from the assumption that the answer to this question is not as obvious as it might at first appear. Clearly, we know some media when we see them: radio, film, and television are in many ways paradigmatic media of the twentieth century. But what about the computational, networked media of the twenty-first century? Are these still media in the same sense, or has the nature of media changed with the emergence of digital technologies? And what, for that matter, about pre-technical media? Is painting a medium in the same sense that oil or acrylic are media, or in the sense that we speak of "mixed media"? Is language a medium? Are numbers? Is the body? As we shall see, the question of what a medium is raises a number of other questions of a theoretical or even philosophical nature. How is our experience of the world affected or shaped by media? Are knowledge and perception possible apart from media, or are they always mediated by the apparatuses, instruments, or assemblages of media? What is the relation between the forms and the contents of media, and how does this relation bear on questions of aesthetics, science, technology, or politics? The course addresses these and other questions and seeks in this way to introduce a way of thinking about media that goes beyond taken-for-granted ideas and assumptions, and that has a potentially transformative effect on a wide range of theoretical and practical interests.

View the full syllabus here.

* * *

Letters of Recommendation

To request a letter of recommendation, please fill out this form only after you have made a formal request via email.

* * *